The past, present and future of the device keeping alive Carew, thousands of HF patients

By American Heart Association News

Editor’s note: Carew, who wore No. 29 throughout his career, is leading “Heart of 29,” a campaign to boost awareness and prevention.

Rod Carew spent his 70th birthday in a hospital. Although he was hooked up to a respirator as he recovered from a heart attack and cardiac arrest, the mood was upbeat. Friends and family brought cake and ice cream. He and his wife, Rhonda, thought they could still visit Italy in a few weeks.

The next morning, everything changed.

Carew’s cardiologist said the baseball Hall of Famer was in severe heart failure. Medicine might help, but probably not enough. A heart transplant might be needed, but in his current state, his body probably couldn't handle it. The best option might be implanting a machine into his heart.

It was Oct. 2, 2015, and if the Carews had ever heard the acronym LVAD, they certainly couldn’t remember it.

Now they can’t imagine a world without it.

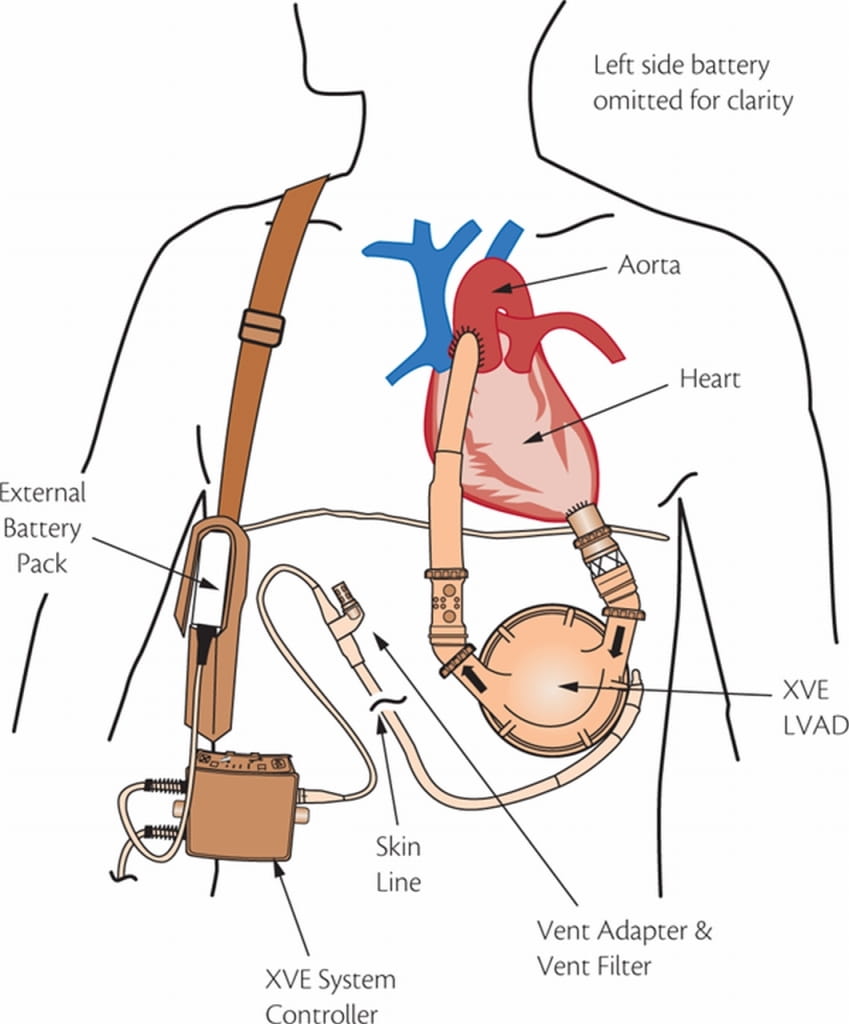

Commonly known as an “L-VAD,” the letters stand for left ventricular assist device. The word “assist” somewhat downplays its role. This plastic and metal device actually takes over the function of pumping blood to the body.

Carew is among tens of thousands of people whose lives have been improved and extended by an LVAD. He’s also among the higher-profile recipients, along with former Vice President Dick Cheney. Cheney received an LVAD in 2010 and a heart transplant in 2012.

As American Heart Association News continues this series of stories related to Carew and his Heart of 29 campaign to boost awareness and prevention of heart disease, this month’s installment looks at the past, present and future of the device that keeps Carew alive.

***

The 1960s stand out as a decade of radical social and cultural change in the United States. It was quite an era for heart surgery, too.

In 1963, an air-powered LVAD was implanted for the first time. It was used for four days and the patient, who was in a coma before the surgery, died.

In 1966, an LVAD was hooked up differently to help a patient recover from the shock of open-heart surgery. The machine was used for 10 days and the patient recovered.

By decade’s end, doctors performed the first successful heart transplant and the first successful artificial heart implant.

In the 1970s, the government began funding studies of LVADs, primarily to help patients recover from open-heart surgery.

More funding, however, went to developing artificial hearts.

Progress on the artificial heart was slow. In the meantime, thousands of people on the transplant waiting list were dying. So in 1980, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute changed its aim. Instead of seeking a machine to do everything a heart does, they invested more into finding one to keep people alive for hours or even days.

***

FIRST-GENERATION LVAD: PULSATILE

The first generation of LVADs were known as pulsatile because, like a normal heart, they had a detectable beat.

Blood flowed into an artificial chamber and was squeezed out to the rest of the body. A version that did so using air, with power coming from a large, external machine, became the first LVAD approved by the Food and Drug Administration. That was in 1994. An electric version that was far more portable was approved in 1995. Both went by the name HeartMate and are collectively referred to as HeartMate I because they’re from the same parent company, Thoratec. Another company, Novacor, also received FDA approval for a first-generation LVAD. (More makes of LVADs from all generations exist beyond those mentioned in this story. The focus here is limited to the most widely used, FDA-approved LVADs.)

While the HeartMate I was a game changer for heart failure patients, they also were clunky.

“A lot of people couldn't tolerate it because it actually compressed the stomach – they had to eat small meals,” said Dr. John O’Connell, a heart failure cardiologist back then and now medical director of mechanical circulatory support for St. Jude Medical, the company that owns Thoratec. “But it gave them a way to stay alive until they got a heart transplant. It kept people alive for 18 months to two years.”

At first, LVADs were designed to be a temporary aid until a permanent one could be found. This is known as a “bridge-to-transplant.”

But around the time LVADs went into circulation, heart transplants in the U.S. plateaued at roughly 2,200 per year. With the population increasing, and the number of heart failure patients also on the rise, folks wondered whether LVADs could be more than a bridge. Could they be a long-term option, or what the medical world calls “destination therapy?”

The National Institutes of Health launched a study to find out.

One group of patients received medicine and doctor’s care while another group received LVADs. Over two years, the LVAD recipients far outpaced the other group in cardiac recovery, survival and quality of life measurements.

The study was published in 2001. In 2003, the HeartMate became the first LVAD approved by the FDA for destination therapy.

***

SECOND GENERATION: CONTINUOUS FLOW

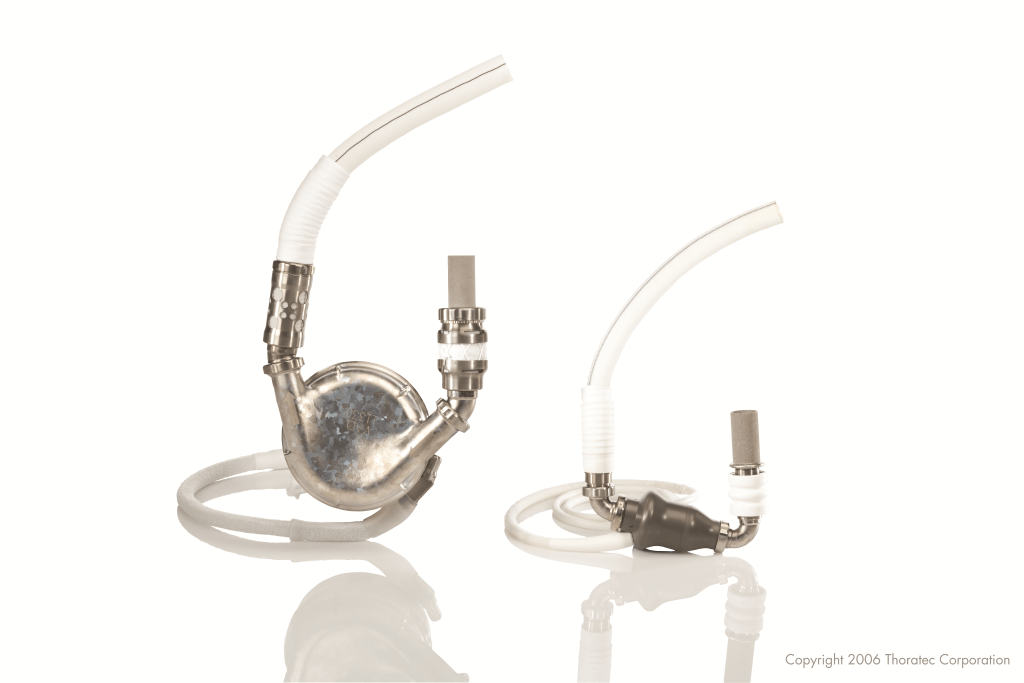

Inside the HeartMate II. Image provided courtesy of St. Jude Medical, Inc.

The next wave of LVADs went from a pump to a stream, or what’s called a continuous flow.

The HeartMate II does this using a rotating screw. Blood comes into the chamber and twists through a device that is smaller and more comfortable than its predecessor. (A quirk of this stream: Recipients have no pulse rate.)

The HeartMate II is the most commonly used LVAD, with Carew and Cheney among 22,000-plus recipients. Some patients from the original clinical trials 10 years ago are still alive, so the longevity of this LVAD has yet to be determined.

How Carew and other HeartMate II recipients are connected to the LVAD. Image courtesy of St. Jude Medical, Inc.

“We went from the HeartMate I, a pump being designed to last 18 months, to a pump that we don't know how long it's going to last,” O’Connell said.

***

THIRD GENERATION: ELECTROMAGNETIC

PHOTO Inside the HeartWare HVAD. Image courtesy of HeartWare.

The latest concept is an improved method of continuous flow. It’s based on centrifugal force, with electromagnets spinning the blood.

The HeartWare Ventricular Assist System, made by HeartWare, does this using a chamber that’s even smaller and with no mechanical bearings. It also fits differently, attaching directly to the heart.

“The blood comes in from the top and goes out the side,” said Doug Godshall, president and CEO of HeartWare. “By having it spin at a right angle, the housing can be flat. That keeps it small.”

In 2012, it became the first of this generation to receive FDA approval for bridge-to-transplant. The company is working toward submitting trial results seeking FDA approval for destination therapy.

More than 10,000 have been implanted. Among the recipients is another former All-Star baseball player: Kent Tekulve, best known as a relief pitcher on the 1979 World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates. He later received a heart transplant.

HeartWare has another, similar device in clinical testing. The key difference – it’s one-third the size of the flagship product, known as an HVAD. The miniaturization version carries the acronym MVAD.

Also potentially joining the field is HeartMate 3. A precursor to that was almost ready in 2006 when the company went back to the drawing board, creating a smaller, simpler version, said Kevin Borque, a vice president of research and design for engineering at St. Jude Medical who has been working on this concept since the start. Already approved in Europe, it could receive FDA approval next year.

***

FOURTH GENERATION? FIFTH?

The future for these devices is not just smaller and smarter. It involves terms like “minimally invasive.”

The idea of not needing open-heart surgery follows the path of other transcatheter procedures already being performed through catheters inserted into arteries near the groin. For instance, heart valve replacements are starting to be done this way.

There already is a model of a minimally invasive LVAD placed under the skin. It is the size of an AA battery and is connected from the top chamber of the heart to one of the big blood vessels via a mini-thoracotomy without cutting the breast bone. This device promises to reduce the complications associated with LVAD and is under further study. This may not work for all patients because it would require a bit of a tradeoff, said Dr. Javed Butler, co-director of the Heart Institute at Stony Brook University and Deputy Chief Science Officer of the American Heart Association.

“It may not provide as much support, but the data are encouraging, and it’s an easier, faster procedure, which may be preferable if some patients who do can do well with partial support,” Butler said.

The leap after that may be a device which is completely inserted through blood vessels without requiring surgery or a device that doesn’t require an external battery and controller. Several challenges in developing such a technology have Butler less optimistic about a time frame, but he believes it could be possible over the next decade.

***

In January, Carew was at the Minnesota Twins’ ballpark for the event that launched the Heart of 29 campaign. Among those who greeted him was Phil Ebeling, the St. Jude Medical executive who helped create the HeartMate II.

“Thank you,” Carew told him.

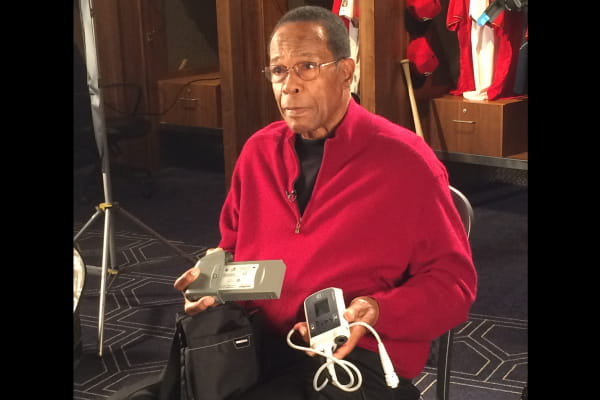

While Carew hopes to go on the transplant waiting list later this year, he knows there’s a chance the LVAD could be his permanent companion. And he’s OK with that.

After all, he knows it beats the alternative faced by heart failure patients of decades past and even by those today who don’t have access to an LVAD. Of the roughly 50,000 people who need a heart transplant, only a fraction receive either a transplant or an LVAD.

“It's tough wearing it and having these batteries all the time,” Carew said. “But, boy, it's a blessing. A blessing.”