Karen's HCM Story

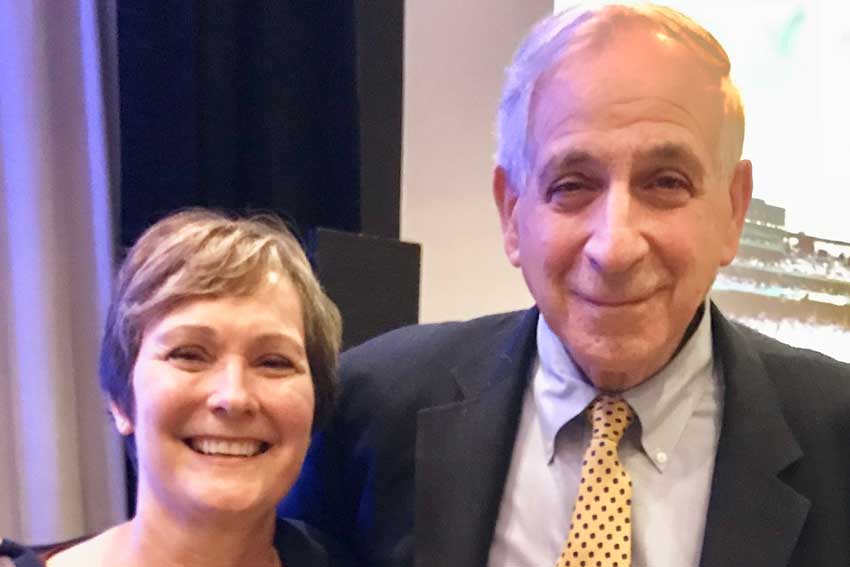

Karen and her cardiologist, Barry J. Maron, MD.

Minnesota woman ‘outliving’ odds of hereditary heart condition is making a difference.

Karen Newstrom jolted awake from what she thought was “one of those dreams where you’re falling.”

Unlike her husband, the mother of five and kindergarten teacher from Minnesota didn’t suspect it was the first of 10 lifesaving shocks from her new heart device.

After the doctor confirmed her heart device was to blame, Newstrom said she couldn’t believe “my husband was right.”

In July 2003, Newstrom was diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, a hereditary condition in which the heart walls thicken and stiffen, making it more difficult for the heart to pump blood. This can cause shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, fatigue, fainting and other symptoms in people of any age.

By August, she got an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, or ICD, to regulate her heartbeat.

An HCM diagnosis might shock many people. But it was nothing new for Newstrom.

“I know that a lot of patients were the first in their families and so it was quite devastating to them,” she said. “But I have lived with HCM in my family for, gosh, a few decades.”

After losing two brothers to HCM, and later losing her father in 2015, Newstrom was keen on the signs and symptoms.

When her son fainted before a pick-up basketball game, Newstrom quickly contacted a specialist. He was later diagnosed with HCM.

Knowing the condition is hereditary, Newstrom and her two youngest children got a cautionary screening soon after her son’s diagnosis.

“I was asymptomatic,” Newstrom said. “And yet, when I went in with the kids that day, I figured that one of us probably would be diagnosed. I was just glad it was me and not them.”

Although her family history prepared her for the physical challenges of HCM, Newstrom has had to navigate changes in her work and social life.

When her HCM became obstructive, blocking significant blood flow, Newstrom could not climb stairs or exert herself. Instead, she had to rely on other teachers to transport her students from one activity to the next.

She also came up with creative ways to talk with her students about her condition. For example, she told them her heart liked to “misbehave.”

“My thought was if something happened during the school day, I didn’t want them to be caught off guard,” she said.

Newstrom also had to make changes in her personal life. When she loses consciousness from an ICD shock, she must give up driving for six months. Often, she has had to ask friends to drive. They’re willing to help, but Newstrom doesn’t want to burden them.

Newstrom said she’s “never felt a single one” of her 10 shocks. Still, the aftermath of the shocks has an emotional impact.

“Every time I awaken from one, I think, ‘I’ve had my life saved again!’ Not just once, not twice. I’m reminded that because of my ICD, I outlived the very thing that caused the deaths of my two brothers.”

Newstrom, an active member of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association for which she leads discussion groups for people with ICDs, said she’s just grateful to be alive.

“Because of that, I try to make some difference with my life each day, no matter how small it might be, whether it be with my family, friends or a stranger,” she said.